About Turkey

With its unique position at the crossroads of Europe and Asia, Turkey has played a pivotal part in the world’s history. The country has acted as a barrier and a bridge between two continents, and became a focal part of a trade route which not only brought prosperity to the country, but laid the groundwork for the rich cultural mix that exists in the country today.

At the Crossroads of Europe and Asia

Turkey is bordered by eight countries: Armenia, Iran, Azerbaijan in the east; by Georgia in the northeast, by Bulgaria and Greece in the northwest, and by Iraq, and Syria. Over the centuries, there have been various struggles, conquests, and changes of power, which have all shaped the nation into its current setting as a gateway between the Middle East, Asia, and Europe.

Turkish culture

Turkish culture has undergone a huge shift in the last 100 years. Before 1923, the Ottoman Empire was a multi-ethnic state. However, it was segregated, and ethnic and religious groups did not mix with each other, retaining their own separate identities. That changed with the birth of the Turkish Republic, however, as the country began to look towards an approach that integrated its diverse cultures to produce one national identity.

Today, Turkey is a modern country with a diverse group of intertwined cultures including Muslims, Jews, Greeks, Armenians and Syrians. There’s also a strong divide between rural and cosmopolitan living, with Turks in the countryside adopting a more conservative way of life, while city-dwelling Turks look to a more modern way of life.

Turkey is home to some 80 million citizens. Three quarters of the population is of Turkish ancestry, primarily progressive Muslims. Turkey is also home to a large population of Muslim Kurds, comprising roughly 18% of the population of Turkey. In the last few years, Turkey has also become home to a high number of Syrian refugees, and around 3.5 million are thought to live in the country.

Turkey’s population is overwhelming youthful, and upwardly mobile. Young professionals are moving to the cities in greater numbers, changing the face of Turkey’s urban centres, and driving its economy.

Turkish history

Before Turkey became a republic, the land was ruled by the Ottoman Empire. The Ottoman state was formed in 1299 with the uniting of a number of Turkish tribes. However, it wasn’t until the conquest of Constantinople in 1453 that the Ottoman state truly became an empire. From that point, until 1683, the Ottoman Empire continued to grow, through a series of conquests and invasions of other territories and tribes. During the peak of the Ottoman Empire’s control of the region, the empire ruled over a population of more than 15,000,000.

The mighty empire began to crumble in the 18th century, as a series of wars took their toll on the Ottomans, who battled on many fronts and with many of its territories.

By World War I, the sun had set on the Ottomans, and 1923 saw the birth of the Republic of Turkey. One of the founders of this new movement was Mustafa Kemal Ataturk. Ataturk was an Ottoman and Turkish army officer who led the Turkish National Movement during the Turkish War of Independence.

After his victory, Ataturk began transitioning the Ottoman Empire into a European Nation-State. He oversaw the opening of new schools, began government reform programs, and lowered taxes. The emergence of this new type of government in Turkey was the start of its growth into a modernised European nation.

Politics in Turkey

In July 2018, Turkey abolished its 95-year-old parliamentary system for one that concentrated all the political power in the office of the presidency. President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, who was inaugurated for a second term at the same date, has radically reshaped a host of laws, regulations and institutions.

The President has the power to directly appoint ministers, many judges and bureaucrats, and one or more vice presidents – taking the place of an elected vice president. Erdogan will also set out the national budget.

While it sounds as if the president has ultimate power, Turkey’s Parliament still holds clout. They have the authority to overturn presidential decrees, and the president cannot overturn by decree legislation that was passed by Parliament. Also, cannot issue decrees in areas that the constitution specifically reserves for parliamentary legislation. This includes criminal penalties, declarations of war, or permission for foreign troops to enter Turkish territory.

Turkey’s geography

Turkey is more than just beaches. The country is home to a diverse and rich collection of landscapes. Surrounded by three seas, Turkey has some 8000 kilometres of coastline. The country is divided into seven geographical regions: the Aegean, Central Anatolia, Eastern Anatolia, Southeastern Anatolia, Black Sea, Marmara, and the Mediterranean region. The largest land area of Turkey is Anatolia, which connects Turkey to Asia. Most of Anatolia is comprised of narrow coastal plains and high plateaus. In the east, most of the land is mountainous and connected to major river systems.

• Total Area: 783, 562 square km

• Climate: Dry and hot summers and mild winters

• Highest Point: Mount Ararat 5,166 m

• Lowest Point: Mediterranean Sea 0 m

These different regions also have varied climates, a feature unique to Turkey. Along the coast of the Mediterranean and Aegean Seas, the climate is hot and dry during the summer and cool and wet during the winter. The coastal regions that lay along the Black Sea tend to be cooler and wetter in the summer than other coastal parts of Turkey.

In inland, elevated areas, snow falls during winter months, which has given rise to Turkey’s ski industry, with ski fields even accessible from Turkey’s Mediterranean coastline.

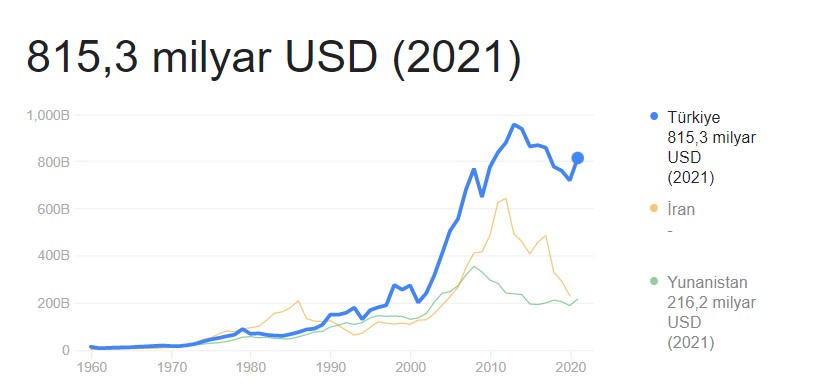

Turkish GDP Grows 9.1% in Final Quarter

With a GDP of roughly US$720 billion, Türkiye is the 19th-largest economy in the world. It is a member of the OECD and the G20, and an increasingly important donor of Official Development Assistance.

Türkiye pursued ambitious reforms and enjoyed high growth rates between 2002 and 2017 that propelled the country to the higher reaches of upper-middle-income status and reduced poverty. The share of people below the US$5.50 per day poverty line fell by three quarters to 8.5 percent between 2002 and 2018.

However, productivity growth has slowed as reform momentum has waned over the past decade, and efforts have turned to supporting growth with credit booms and demand stimulus, intensifying internal and external vulnerabilities. High private sector debt, persistent current account deficits, high inflation, and high unemployment have been exacerbated by macro-financial instability since August 2018.

The Government’s economic policy response to COVID-19 was swift but focused on loose monetary policy and rapid credit expansion. This supported economic activity — Türkiye’s economy was one of the few in the G20 and OECD to experience growth in 2020—but also fueled inflation, which is expected to be close to 20 percent in 2020.

The COVID-19 crisis has also deepened gender gaps and increased youth unemployment and the poverty rate. The risk of inequalities has also been increasing. The pandemic is expected to have severely negative consequences for Türkiye, further weakening economic and social gains.